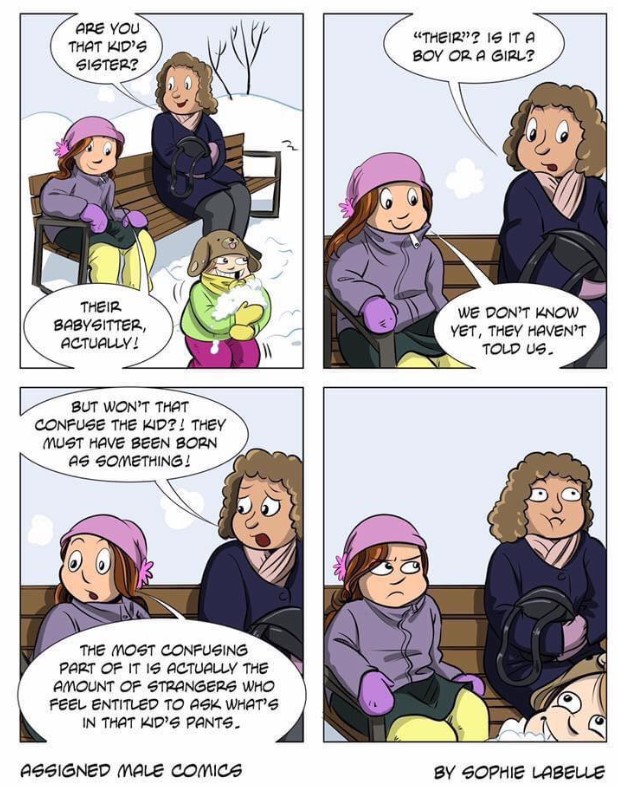

Panel 1: The other person asks the babysitter, “Are you that kid’s sister? “Their babysitter, actually!”

Panel 2: The other person says, ‘”Their”? Is it a boy or a girl?’

The babysitter replies, “We don’t know yet, they haven’t told us.”

Panel 3: The other person says, “But won’t that confuse the kid?! They must have been born as something!”

The babysitter says, “The most confusing part of it is actually the amount of strangers who feel entitled to ask what’s in that kid’s pants.”

Panel 4: The child looks happy, the other person looks embarrassed, and the babysitter looks sad.

Credit: “Assigned Male Comics by Sophie Labelle”

I didn’t know the word, but as a very young child, I knew that my dad was a patriarch. I was four years old when I knew my parents were trying for a son. Dad had adopted two daughters, my two older sisters, who mom had from prior relationships. As the first biological child of both parents, I was supposed to be a boy. With my next sister, the fourth child assigned female at birth, they were also hoping for a boy. When my parents tried once again and finally got a boy for child number five, everyone expected them to be done having children.

Up until that point, they themselves said they would be done once they got a boy. However, as dad recounted many times later, that was when “God told us to keep having children.” Mom miscarried before having two more boys, just over a year apart – in July 1997 and August 1998.

When dad would leave for work in the morning, he’d overlook his wife and all four of his oldest daughters and turn to his eldest son. “You’re the man of the house while I’m gone,” he would say to the little blond toddler with trusting blue eyes. As he grew, my little brother took this designated role to heart. He believed that he should get his way and make decisions because “I’m the man of the house.” My mom deferred to her oldest son because she agreed with deep religious conviction.

After singing each baby a lullaby and gently placing them in their crib, my mom would say a prayer for their future spouse – a husband or a wife, depending on the baby’s sex. From cradle to grave, we were expected to have a cishet (cis=not trans, het=heterosexual) life that brought honor to our family.

My parents assigned gender to their children as soon as they could see our genitals. I distinctly remember a home birth where nobody got a glimpse of the baby’s genitalia until they were turned around. For one brief moment, that baby was just a baby, not defined by what was between their little newborn legs. That moment was filled with voices as my parents and the midwife fumbled to adjust the still-wet infant, umbilical cord not yet cut, saying “what is it? What is it?”

Patriarchal culture is obsessed with genitalia. Without terms that colloquially refer to someone’s genitals, nobody knows what to use as a personal identifier. Boy or girl, sir or ma’am, Mr. or Mrs., man or woman – all of these terms are just labels that mean “penis” or “vagina”. Explicit names for genitals are taboo. Meanwhile, a myriad of terms exist to imply that people are defined by their genitalia. People who assume patriarchal standards will adamantly deny this fact.

Queer culture is not obsessed with genitalia. There is a full spectrum of identity and attraction. In queer culture, the only people who need to know what’s between your legs are your doctor and sexual partners. Parents don’t announce their baby’s genitals to everyone and host gender reveal parties. It is considered rude to ask a trans, intersex, or non-binary person what sexual organs they have. In queer culture, nobody needs to know whether an infant or young child fits the patriarchal binary.

While patriarchal society uses code terms to subvert its emphasis on genital conformity, its adherents project their obsessions onto queer culture. We want children to have bodily autonomy and identity expression. People who insist on prioritizing patriarchy will go so far as to subject children to genital inspections to make sure they fit the binary divide. Who wants to look at children’s genitals for non-medical reasons? This perversion is found in patriarchal culture, not queer culture.

There is a specific set of expectations for sons of patriarchy, but I want to address the mold I was expected to squeeze myself into because I know it so well: the role of the daughter. I am non-binary, meaning I am neither a man nor a woman. For most of my life, I was referred to in terms that assume I have a vagina – girl, daughter, someone’s future wife. That comes with it all the expectations of that category in a patriarchal culture. Anyone born with a vagina must marry someone born with a penis, and after they’ve completed the ritual of marriage, they can start to produce offspring. Any deviation from this is met with extreme shame.

In this series, I will address the question of how daughters are brought up to embrace their own oppression under patriarchal rule. I will explain the dynamics that allow patriarchy to thrive in denial and secrecy. I will also discuss how the division of labor – and who gets credit for it – applies to patriarchal norms. In highlighting these aspects of patriarchal culture, I hope to demonstrate how poisonous it is for those trapped in its clutches. While I’m glad I escaped the extreme version of it that I was raised with, I want to emphasize that patriarchy is normalized across the world. Even in mainstream American culture, patriarchy is the generalized expectation. To truly overthrow the patriarchy, we must identify and name its pervasive elements. I hope that this series will help to do just that.